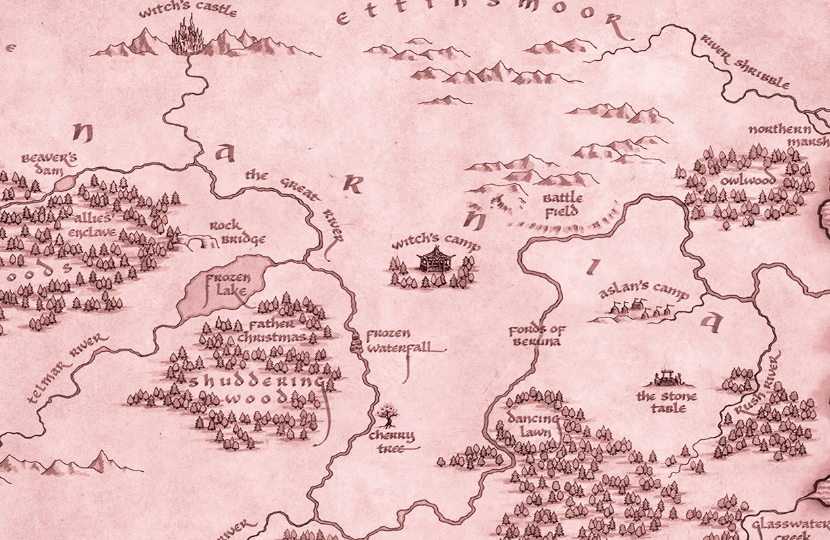

In C.S. Lewis’ fantasy novel series, The Chronicles of Narnia, an atmosphere of vigilance is delicately built by the author through a description of trees being spies for Jadis, the White Witch. The character Mr Tumnus insists upon speed and silence during a short journey, fearing the consequences of being surveilled by an unknown variable. His anxieties are well-founded; Mr Tumnus later finds himself arrested, imprisoned, and turned to stone as punishment.

63 years after the publication of The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe, Edward Snowden blew the whistle on government spying through surveillance programs that collected telephone records and internet communications. The Snowden leaks enlightened citizens to spying and dramatically altered the course of state surveillance by igniting legal challenges against previously unknown interception programmes (while the outcomes of these legal challenges have been mixed, they have forced governments to admit to previously secret practices and have thereby opened up avenues for policy reform).

By passing through the wardrobe into the intrusive world of surveillance, it becomes impossible to maintain the blissful ignorance of a private life. The position of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) is that the existence of legislation granting powers of secret surveillance is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security and for the prevention of disorder or crime. Nonetheless, it is argued that the state has assumed powers to lawfully access communications without public consultation or consent, contradicting the principles of democracy.

Law, while legitimating surveillance technology, is ambiguous, as well as generous in favour of the side of the government, creating ‘gods of interception’ who possess powers beyond the wildest dreams of most citizens. The power placed within some officeholders is excessive, this essay further argues, and the existence of backdoors, overrides, and loopholes within legislation means the law does not effectively and properly control surveillance.

As far back as 2002, it was estimated that 25 million people had access to the World Wide Web; the estimated ‘digital population’ of internet users in the present day is five billion. The evolution of digital computing has increased citizens’ reliance on communication technologies, bringing benefits such as reducing errors and increasing efficiency. Inevitably, communication technologies have been exploited for illegal purposes. The existence of the EncroChat messaging service, the infiltration of which led to prosecutions of significant crime groups, is an apposite example of the criminal usage of modern communication technologies. Encrypted data platforms are legal and have a multitude of genuine uses, but in the case of Encrochat, the service was used by allegedly criminal organisations for encrypted and covert communications.

Increased use of the internet to accomplish electronic commerce, information acquisition, and community operations prompted the replacement of the ICA with the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) 2000, a maze of legislation containing 83 sections along with 5 complete schedules. RIPA claimed to provide a new and comprehensive regime governing surveillance, the interception of communications, and the decryption of encrypted material. The ‘hastily drafted and ill-conceived’ RIPA may have been part of a government attempt to encourage internet use, allaying fears concerning its security and trustworthiness.

RIPA was designed to take account of new technology and ensure conformity with the European Convention on Human Rights. The human right to privacy must be ring-fenced, with the protection placed around an irreducible core of the right. While this ring fence may appear to exist in the form of legislation, it remains unfit for purpose, as evidenced in 2013 by the revelations of Edward Snowden. Snowden, seen as an ‘Aslan’ of privacy rights by supporters, informed citizens that they were being spied upon by their own governments, with the British security service secretly collecting a vast amount of phone data under the authority of legislation including the Telecommunications Act 1984. Snowden‘s disclosures revealed previously-secret programs such as PRISM, which could directly access the servers of US internet giants to collect conversations, files, and search history, and Tempora, a British system that intercepted internet traffic being passed through fibre-optic communication cables.

It is theorised that the arbitrary power of GCHQ to access bulk interceptions (such as those provided by the NSA) could have been used to circumvent section 8(1) of RIPA, resulting in the avoidance of privacy-protecting safeguards. In essence, if GCHQ was unable to show that it was necessary and proportionate to target an individual with a warrant, there was nothing in law to prevent unwarranted surveillance using PRISM instead. While RIPA is, by name, supposed to regulate (by definition, this word means the control of an activity or process), the interpretation of this legislation is stretched to allow an array of activities that have not received Parliamentary approval. The successor Act, the IPA, legislates on powers to collect information through the retention of bulk data; this is possible through warrants to gather data from communication channels, allowing for monitoring of individuals without their knowledge.

While the IPA does provide a layer of protection by stating there must be oversight by an appointed Judicial Commissioner of warrants, there remains a need for supplementary tests. The Investigatory Powers Act 2016 is a step closer to the full legalisation of bulk state surveillance, where the gods of interception would be free to sidestep safeguards and go against the public view that certain surveillance technologies compromise human rights and are abused by security agencies. Under the IPA, internet connection records can be accessed by some authorities without a warrant (the list of authorities, for reasons not comprehensible, includes the Gambling Commission).

The disclosures of Edward Snowden also shed light on intelligence-sharing routines. One instance is that of a deal reached in principle in 2009 by the NSA and the Israeli SIGINT National Unit. The NSA routinely provided the Israeli intelligence unit with raw data about US citizens; the intelligence data was neither sifted nor redacted, and no legally binding limits were placed on Israeli use of the data. The Memorandum of Understanding put in place to prevent Israel from targeting US citizens using NSA-provided data was not a legally binding document and explicitly stated that it was ‘not intended to create any legally enforceable rights’. It is argued that the trading of intelligence with other countries without a legally binding agreement discredits the operation of a democratic political system, maintaining a ‘culture of mistrust amongst citizens’.

The Narnian representation of the state, the White Witch, was not trusted by the citizens of that realm; nor do British citizens in a post-Snowden era, who do not trust the government to behave responsibly. The UK government has invoked British public opinion as ‘probably being prepared to give up privacy to enhance security’. Surveillance law has not been passed without obstacles; the Data Retention and Investigatory Powers Act (DRIPA) 2014, which regulated access to communications data and required the retention of this data by telephone and internet companies, was a rushed emergency law that did not make it past the Court of Appeal. DRIPA allowed access by public bodies to personal details even when there was no independent sign-off or suspicion of serious crime. For powers of interception to exist in an acceptable way, independent scrutiny must ensure that abuse cannot happen under the guise of necessity.

DRIPA is an example of legislation that provided no real benefit to the common citizen, given the Act did not lay down clear and precise rules providing for access to and use of communications data. The vague term ‘serious offences’ was used within the Act without any definition, essentially providing the government with a blank cheque for investigation of potentially crime-related communication material. The Act did also not provide for judicial scrutiny regarding the examination of only ‘strictly necessary’ data, presenting another issue relating to the abuse of interception powers by the gods of interception and those working on their behalf.

The Chronicles of Narnia series is not unique in describing a regime in which surveillance is normalised. Other references to state surveillance are easily findable within popular culture, whether it be Orwell’s Big Brother in 1984 or an AI-based intelligence supercomputer in the 2008 surveillance thriller film Eagle Eye. Another is the notion of a Nine Eyes Committee, which exists to provide intelligence to criminal organisations in the 2015 Bond film Spectre. Unlike its real-life counterpart, the Nine Eyes Committee includes China, a country that has a reputation for human rights violations. The idea of an expanded collective is not beyond belief, and with the documented rise in state surveillance across the globe, there is a danger that individual privacy could become a thing of the past. There has also been an expansion of routine requirements for the sharing of large amounts of citizens’ personal information; this is known as ‘dataveillance’.

The term ‘gods of interception’ is featured to refer to selected officeholders (and those working on their behalf) possessing unique and sometimes excessive interception powers. There is a class-based criticism to be made regarding these officeholders, who will often be from a similar background of privilege; for example, according to the Google search engine, every Director General of the security service since 1988, with only one exception, has been privately educated. It can be argued that legislative safeguards around state surveillance have only been added when the government has felt forced by the courts, or as a response to an unprecedented situation such as the 2013 Snowden revelations. There is a benefit to be found in increasing policy consultation on the matter of surveillance.